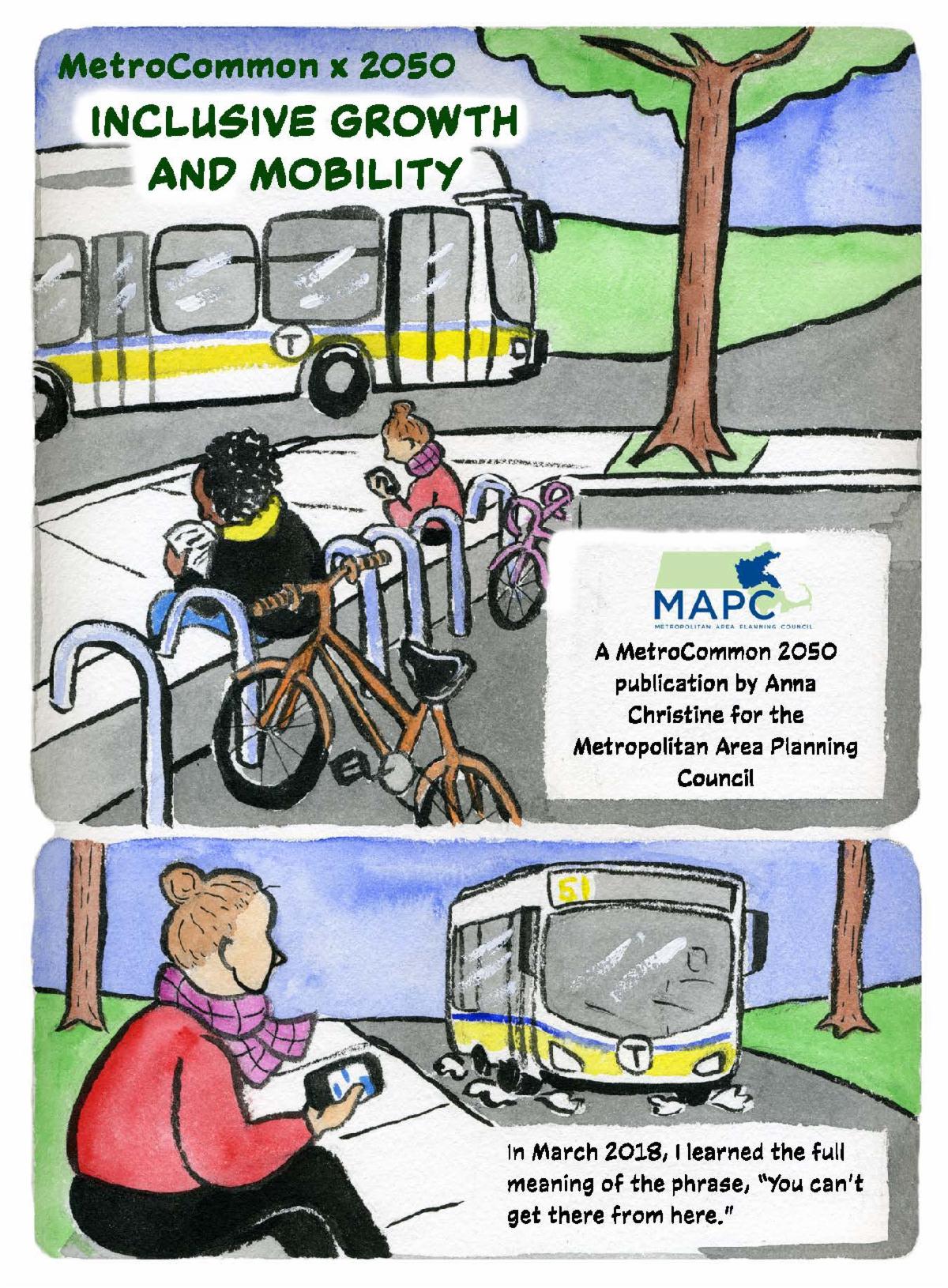

Inclusive Growth & Mobility

- The Vision

- Policy Recommendations

- How We Got Here

- Challenges

The Vision

- the ways we get around are reliable, adequately funded, and well maintained. Travel is safe, efficient, pleasant, and affordable to all households, regardless of income. New transportation technologies and services operate on our roads, underground, and on the water. These new travel options help alleviate congestion and pollution, rather than adding to it. Public transit and shared trips are often more convenient and affordable than solo trips. Auto congestion still exists, but it is predictable and avoidable.

People with mobility limitations and those without a car can get around easily and can afford to do so. Low-income residents and residents of color enjoy high quality transit to more parts of the region, improving access to opportunity. People of all ages walk or bike more frequently for short trips because conditions make that option safe and enjoyable. The transportation system has a minimal impact on the local and global environment, with reduced pollution and runoff, drastically reduced GHG, and less land set aside for roadways and parking.

- our air is pure, indoors and out. Our cities and towns are healthy, with beautiful parks and natural areas accessible to all. Our cities and neighborhoods are quieter, with less polluting and more efficient transportation technologies. Contaminated sites are cleaned up and turned to new uses. There is less waste overall, but unavoidable waste produces energy, fertilizes soil, or is reprocessed. We have enough fresh water from our wells, streams, and reservoirs to meet the needs of people and wildlife. Our farms and fisheries produce plentiful and healthy yields, and are sustainable. Habitats, forests, wetlands, and other natural resources are protected and enhanced.

- residents and visitors of all backgrounds enjoy a wide variety of historical, cultural, recreational, and artistic experiences. Public art, cultural institutions, and social activities reflect our region’s diversity and an accurate reflection of history. Residents of all ages, abilities, and incomes have opportunities for creative expression and art education. Public and private funding makes art more accessible to a broader audience. Public programming and urban design encourage opportunities for social and cultural experiences and walkability. This builds social connections and cohesion. New development complements and enhances existing city and town centers. Historic buildings and cultural landscapes that are important for understanding our region’s people and cultures are protected or adapted to contemporary needs.